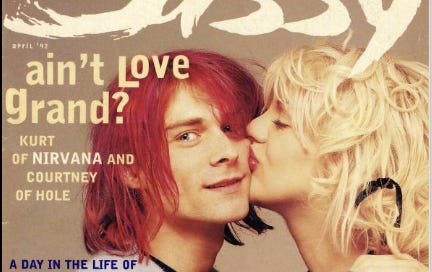

Like many GenXers, I first learned about zines through Sassy magazine (I still miss you bb). Sassy magazine was itself something of a zine gone corpo, full of mismatched fonts, cut and pasted articles, scribbles, handwritten text, and DIY inspo for disaffected youth who spent their free time listening to the Pixies while altering their GAP jeans with sharpies and scissors and dying their hair pink with Manic Panic. There was no internet back then, just penpals. Zines were a way to connect with people all over the world who were just as weird as you!

Back then you’d put actual cash or coins (usually a dollar or so) in an envelope and mail it to the zinester. In about a week you’d receive the zine. That zine would usually recommend a few other zines so you’d send away for those too if they sounded interesting -- wash, rinse, repeat -- and before long your mailbox was full of more zines than you knew what to do with.

Zines back then were simple – generally black and white collaged images, handwritten or typewritten text, folded, and stapled closed for mailing. Fancy zines were printed on colorful paper. Extra fancy zinesters added artwork after the zine was copied, turning each zine into a one-of-a-kind piece of art.

The other day Miquela Davis wrote about a zine show experience:

“It really highlights a growing problem I am seeing in the zine world: of zines becoming more and more art books produced by printing companies rather than artist made materials for self expression, fighting oppression, circulating information (especially in a fascist regime), and being by the people for the people.”

This bit resonated with me, because I noticed the same thing at a zine show at Dale Zine during Basel this year. The zines there were, generally speaking, professionally printed, art directed, and sanitized to a degree that they were more small press art books than DIY expressions of creativity and connection. This is fine! Much of what Dale Zine does is community oriented. Like many small presses, it teaches classes and creates opportunities for artists and writers to show and sell their work. In order to do that, they need to generate sufficient revenue to maintain a storefront in Miami (theirs is in the Design District, nestled in amongst Tiffany, Brunello Cucinelli, Veronica Beard, and Cult Gaia). Artists having zines professionally printed by small presses support the larger mission.

But this called to mind the way our understanding and appreciation of handmade goods has evolved over the years, in large part due to Etsy co-opting this culture for corporate gain. In the beginning, Etsy was a scrappy startup that truly valued artists, crafters, and makers. It heavily promoted bespoke, high-quality work and we were encouraged to price our offerings accordingly. Things made by hand take time, talent, and attention, and Etsy promoted makers who listed high-quality creations. Etsy wanted our shops to function as mini boutiques; our packages to feel like gifts when they were opened; and our customer service to be attentive and professional. As we put more effort into our listings, we raised our prices. Nobody wanted to be considered the “bargain” option on Etsy.

And then they went public.

And then came the million dollar a year “handmade” Etsy businesses. When you answer to shareholders you need to do volume, which means you need to abandon your ethos and pretend that assembling and embellishing mass-produced goods is the same thing as creating them by hand: “[T]he knitted legwarmers, socks, and gloves, are sourced wholesale from India. ‘We finish them here, adding lace trimmings and buttons,’ Shaffer says. The profit margin from such imported items is 65%.”

Walking to work one morning I passed Septa bus with a giant Etsy advertisement plastered to the side: “Handmade for less,” next to a picture of a happy woman wearing crochet.

Fuck. Etsy.

People who sold actual handmade things – crochet hats, knitted socks, hand-carved home décor, handmade books – were abandoned by Etsy. The only way crafters and makers could compete was to devalue their work in a race to the bottom, price-wise, that has never ended. That, or buy a Cricut and embellish t-shirts; or design mugs and use a drop shipper; or generate shitty AI art and call it junk journaling supplies; or buy a bunch of plastic Temu shit, slap a sticker on it, and resell it; or when all else fails sell an e-course (written with AI, natch) on how to be successful on Etsy, whatever success there even means at this point.

People are so busy being #girlbosses in their phones I’m not sure they even notice or care, because Etsy demands artists and crafters to feed the beast - providing less and less support while demanding ever-increasing fees. If you’re not doing volume and paying Etsy promotion fees, you’re invisible in search results. The end result is a flattened “handmade” culture devoid of anything that even resembles things made by hand. Have you been to a craft show lately? They’re full of embellished knockoff Stanley tumblers and pyramid scheme vendors and it’s just so gross and sad. This is another rant for another day, though – let’s do Substack (also looking at you, Medium)!

Substack had a short on-ramp to VC funding, so it’s never really been a scrappy startup like Etsy. It has a laser-focused mission: bring writers (and now content creators) with huge followings to the platform so that Substack can ramp up revenue at scale. It doesn’t offer much support to early-career writers or even established writers bringing smaller email lists. The writers using Substack are doing the heavy lifting of building Substack’s brand (for free!!) by describing themselves as “Substack writers.” You can’t swing a cat without hitting an article teaching you how to build a successful Substack, or to write better, or to use Notes strategically. This is all very Mediumesque, IYKYK. I suspect if you did a Venn diagram there’d be a lot of overlap among writing coaches who migrated from Medium to Substack to do the same thing in the new place.

The aggravating thing is that if you had a website or a blog back in the early 2000s, you already know how this is gonna go.

Blogs started out as the place we went for self-expression and community building. We talked about our life, our hobbies, our kids, our jobs…whatever bounced into our brains was fair game for writing. They were essentially online diaries. We created webrings to form networks of people who shared our interests and connected with new friends through online forums (I miss you Craftster!). We left comments on people’s posts and cultivated friendships. We were curious enough about the handful of people in our network that we noticed if they hadn’t posted for a while and we checked in on them.

Enter the blogging coach. We were encouraged to niche down, narrow our interests, plaster our websites with advertising to make money, join affiliate marketing networks, add a downloadable freebie to our email subscription pop-up, adhere to a content calendar, create an email marketing plan to grow your list, etc. The internet was soon overrun with “personal blogs” that looked like small businesses, each of them dutifully sharing their income report at the end of the month to show others how easy and profitable blogging was. It was almost a relief that social media came along and wiped the personal blog off the map. By that time it was obvious that most of them only existed to make money so…they were boring and they sucked.

As I’ve talked about before, Substack is a useful tool. But it’s also a very flat expression of what art and writing can be, and that’s only getting worse as more people join the platform and follow the advice of “professional Substackers.” To wit, my inbox on Sunday morning. (Yes, I sometimes send an email out on Sunday morning, but that’s because I only send emails when I have something to say, not as part of any overall strategy, I do not have one lol!) I imagine before too long reading Substack newsletters will be as boring and tired as Medium and Etsy and personal blogs.

Part of this is on us – the artists, the writers, the makers – because we fail to acknowledge that these “easy mode” business tools provided by Etsy, social media, and Substack weren’t designed to help us. They were created to extract value from us. These platforms need us to keep building bigger businesses and chasing larger reach in pursuit of more money not because they are excited to see our creative efforts grow into Big Brands, but because their shareholders demand ever-increasing profit margins. We abandoned our DIY ethos in service of capitalism and we will continue to pay the high cost of low prices forever and ever amen until we decide – individually and collectively – to once again commit to valuing our work appropriately and accept that quality and connection with real community is more important than doing numbers and making as much money as humanly possible.

Professionalism + scale = success is a lie we’ve been sold by people who seek to extract value from our labor.

This brings us back to zines and the way companies and creative organizations are co-opting our work and flattening zine culture by nudging us to make more “professional” looking zines and turning them into publications worthy of valuable shelf space in stationary shops and bookstores. It’s tricky, because small presses are absolute fucking gems. They are community hubs and maker spaces, and they do a lot of heavy lifting for independent artists and writers. We want to support them, and one of the ways to do that is by using their printing services (obvs!).

We can have gorgeous small art books AND we can also continue doing our scrappy lil DIY zines. It’s important for us to have both because it keeps everything – small presses, access to information, community – accessible. Options are good. For some artists, learning how to grow from zine to publication is a fun creative challenge or a business goal. But also, it’s important for the “institutional” zine community to continue to support handmade zine culture by giving DIY zinesters equal space and attention. It’s important that artists don’t feel pressured to abandon their creative vision by influencer culture and the rise of “zine coaches” (trust me, they’re coming!) and it’s important for zinesters to feel supported by their community.

I’m watching this happening with junk journaling right now. What started out as a creative way to repurpose literal trash has been repackaged and sanitized into Grabie’s “junk journal” kits and Pipstickers “junk journal” stickers so they can be shilled on weird QVC by content creators chasing those sweet sweet influencer dollars. If you look at junk journals on Instagram now as compared to ten years ago, you can see clearly the way DIY culture has shifted under the influence of capitalism.

If we’re not mindful of this influence the same will happen to zines. That will be a great loss to us all.

Know what I'd like to see? A site totally dedicated to Zines. I don't have the time to set one up but would definitely support it. 🙏🫤😍

Omg thanks for writing this, I just made the first issue of my zine and have been wondering a lot about what zine culture was like pre-internet and now I want a p.o. box lol